Peter Ungphakorn

Anytime soon, the World Trade Organization (WTO) is expected release a ruling on whether Australia’s law on plain packaging for cigarettes and other tobacco products is legal under WTO law.

The ruling is being watched around the world — from Thailand, Indonesia and New Zealand, to the United Kingdom, Ireland, Cuba and Uruguay — as a growing list of countries have introduced or plan to introduce similar anti-smoking laws or regulations. For their part, tobacco producers fear another setback for their farmers.

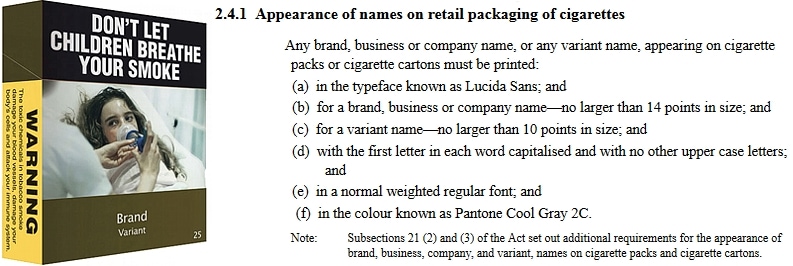

Australia’s law broke new ground when it was passed in 2011. It did more than require health warnings and lurid pictures on cigarette packs. It attacked the key marketing tool of “branding”. For the first time, all brand names had to use the same font and size, on identical packaging that uses colours chosen because they are unattractive.

In May this year, a similar law came into effect in the United Kingdom. In the pipeline are New Zealand, Ireland and France.

The reaction by the tobacco giants was swift and global. It included a number of legal challenges, including in the WTO.

For some, the WTO case has broader implications. They see it as a test of the accusation that the WTO places trade above health and other concerns. In fact this has been tested before, for example when the WTO upheld an EU ban on asbestos products.

In this case, according to press reports in May Australia’s health concerns may indeed be upheld above trade concerns. (The reports were apparently based on leaked information from a draft given only to the countries in the dispute so they can comment on the facts in the document, not the legal arguments.)

But as with everything in the WTO, the details of the case are a lot more complicated than that. This article is not an analysis of the ruling itself (it was written before the ruling was released). Rather, it looks at the background and what the implications of the ruling might be.

Points to remember

Four important points are worth keeping in mind.

First, “WTO law” is not imposed on countries. It is essentially a set of agreements, negotiated and signed by WTO member governments — our governments.

Second, consensus is needed for a deal to be concluded, meaning WTO agreements are generally compromises so that the deal can cover a wide range of concerns. Deals typically aim for particular trade objectives but they will also include flexibility and exemptions, and they recognise a range of other priorities, including health. It’s all about balance — between trade and those other objectives.

Third, the ruling is not necessarily final. It can be appealed. Both sides in a case often do appeal because a ruling also interprets the agreements, which means it creates case law. In this case the ruling may set a legal precedent on whether, to what extent and why public health is — or is not — more important than trade (although the two are not necessarily incompatible).

Fourth, WTO disputes are complicated because WTO law is complicated. This one involves several agreements, each with its own compromises between different objectives.

Most of us want to know: “Who won?” Lawyers are reluctant to talk about winning and losing in WTO disputes because most rulings uphold some points and reject others, so sometimes both sides claim they “won”.

Here, most people will only be interested in whether Australia can keep its plain packaging law. Some will also want to know whether it needs to be modified. A few will want to know why. They will be the ones who really understand.

In the WTO

Australia’s legislation was signed into law on December 1, 2011 and took effect a year later. Already since June 2011, plain packaging for tobacco products had become a regular item on the agenda of two WTO bodies:

- the council dealing with intellectual property (TRIPS or Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights — trademarks, geographical indications, etc.)

- the Technical Barriers to Trade Committee (TBT, whose coverage includes labelling and packaging requirements as possible trade barriers)

WTO councils and committees consist of all WTO member governments and serve to monitor how well the relevant agreements are being implemented. In this case, the two bodies started their discussion with Australia’s legislation and continued over the weeks and months as New Zealand, Ireland and the UK prepared similar laws.

Then, four months after the Australian law took effect, in March 2012 the first of five legal challenges was launched.

The countries involved are intriguing. Some are among the poorest in the world, and not normally known to splash out on expensive litigation. One doesn’t seem to have a stake in tobacco trade at all.

This might partly be explained by the fact that only governments can bring legal challenges in the WTO, not companies. Almost certainly the big tobacco firms were behind at least some of these challenges.

First, Ukraine surprised the world by launching the first legal challenge in the WTO (dispute settlement case DS434). Ukraine is neither a major exporter of tobacco products nor a tobacco grower.

Next came Honduras a month later (DS435), Dominican Republic in July (DS441), Cuba the following May (DS458) and Indonesia that September (DS467). All four produce tobacco and tobacco products.

The list of countries claiming third-party interest in some or all of these cases is unusually long: Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, EU, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Japan, S.Korea, Malawi, Malaysia, Mexico, Moldova, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Norway, Oman, Panama, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, Ukraine, US, Uruguay, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Some are concerned about the impact on their tobacco farmers. Others are tightening their own tobacco controls. (Interestingly, Switzerland is not on the list: it hosts both the World Health Organization, which favours plain packaging, and important offices of some tobacco companies, which, naturally, don’t.)

The five cases were merged and a single panel of three experts was appointed to examine them. Then, Ukraine’s case faded from sight as mysteriously as it appeared. Ukraine asked for the panel’s work to be suspended and then fell silent meaning the panel’s jurisdiction on Ukraine’s complaint expired in 2016.

It is the ruling on the merged remaining four cases that is the centre of attention.

Three core issues

WTO disputes are first examined by a panel of three experts who act in their own right, without representing or serving any country. Appeals are examined by a sub-group of the seven appeals judges (the Appellate Body).

Rulings are adopted by the full WTO membership in its Dispute Settlement Body. They can only be rejected by a consensus of the membership. This has never happened because it would mean the country winning the case (or winning its key legal points) would also have to agree to reject what it had won.

Although other WTO legal provisions have been brought into this case, the focus is on three issues — two on intellectual property (trademarks and geographical indications) and one on labelling and packaging. In each, the main question is whether restricting WTO rights can be justified in order to protect public health:

- Trademarks. The complaining countries argue that plain packaging deprives companies of their right to use trademarks. They also argue that this reduces consumer choice, and is counterproductive because the packaging is easier to forge, encourages smuggling and does not reduce smoking, and may worsen public health. Australia (including in this evaluation) and the World Health Organization (a WTO observer) reject the argument.

- Geographical indications. These are special names used to identify the origin and characteristics of products, such as Cuban cigars and Indonesian clove cigarettes. The arguments are similar to those for trademarks.

- Labelling and packaging. The Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement says regulations should not restrict trade more than necessary to meet their objectives. Essentially opponents of plain packaging claim either that it fails to meet the objective (doesn’t reduce smoking or improve health) or that other, less restrictive measures could achieve the same result.

The arguments in more detail will be in the panel report.

Outside the WTO

Outside the government-only constraint of WTO dispute settlement, the tobacco companies have taken litigation and other action into their own hands.

In 2012, the Australian government won a case in its High Court brought by British American Tobacco, Imperial Tobacco, Philip Morris and Japan Tobacco. They claimed that by depriving a company of using its intellectual property (trademarks), plain packaging amounted to confiscating property. The court ruled that preventing the use of intellectual property was not the same as seizing property. The tobacco companies were also ordered to pay costs.

Three years later, in 2015 Canberra won an international commercial arbitration case brought by Philip Morris citing an Australia-Hong Kong investment agreement. Philip Morris’s claim was similar to the High Court case. Philip Morris was also ordered to pay costs.

Last year, Philip Morris lost a third case it brought against Uruguay for various tobacco control measures. Uruguay’s measures are not about plain packaging because brand logos are still allowed but the controls included large health warnings on packets and banning words such as “Lite”.

Incidentally, these outcomes challenge the accusation that when companies prosecute governments (known as investor-state disputes) the companies inevitably win.

The tobacco companies continue to face accusations of bullying against smaller countries wanting to introduce controls, such as in Africa and South Asia. (This report in the Guardian and this one from Reuters were published only a few days ago.)

A bit of history

Finally, a bit of history. In 1990 Thailand lost a case brought by the US under GATT (the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade), the WTO’s predecessor. Thailand’s ban on imported cigarettes was ruled unjustifiable on health grounds partly because Thailand was inconsistent in allowing domestically produced cigarettes to be sold — the ban discriminated in favour of the Thailand Tobacco Monopoly. The ban on advertising was upheld, however, because that applied to all cigarettes, not only imports.

In the WTO era (since 1995), Thailand has lost another dispute over cigarettes, this time brought by the Philippines (DS371). The case was purely about trade principles: again Thailand was found to discriminate against imported cigarettes, for example because domestic cigarettes are automatically exempt from value added tax while imports are not. The Philippines continues to complain that Thailand has not implemented the ruling.

WTO (and GATT) dispute panels are more comfortable with trade violations such as discrimination, than cases where they have to assess non-trade objectives such as public health. For Australia’s plain packaging it’s an issue the panel cannot dodge.

Want more?

- John Oliver is always fun

- Plain packaging is not just about cigarette packs. Everything from the cigarettes and cigars themselves to cartons, boxes and tins is covered. Full details of Australia’s requirements are here

- Just how busy was the WTO with this issue until it became a full-blown legal dispute? This chart covers June 2011 to February 2015 (pdf)

Peter Ungphakorn is based on the shores of Lake Léman in Switzerland. He spent almost two decades with the WTO Secretariat, Geneva. Before that he worked for The Nation and the Bangkok Post. He now blogs on trade, Brexit and other issues at https://tradebetablog.wordpress.com/