Peter Ungphakorn Story

Papimol Lotrakul Illustration

[box]Brexit has almost completely dominated British politics. A strange calm briefly interrupted months of hectic activity, but not for long. Peter Ungphakorn considers five lessons learnt so far. Part 1: Red Queen Theresa’s Race

[/box]

For months, the United Kingdom’s chaotic efforts to set up its departure from the European Union (Brexit) saw almost daily twists and turns. Tension mounted and the British moved ever closer to crashing over the cliff-edge and out of the EU, with only the flimsiest of parachutes.

Members of the British Parliament were under round-the-clock pressure. They were the target of torrents of abuse. Several received death threats — taken seriously since MP Jo Cox was murdered by a right-wing extremist during the 2016 Brexit referendum campaign.

Exhausted and stressed-out, they struggled mentally and emotionally to make rational decisions as over and over they debated and voted on the same issues.

Finally, early on April 11, for a second time the EU agreed to postpone the date of the UK’s exit. It was originally March 29 under Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union — which governs an EU member’s departure — two years after British Prime Minister Theresa May triggered it.

The UK is now scheduled to leave the EU by October 31. Theresa May wants to do it by June 30, so that newly-elected British members of the European Parliament won’t have to take their seats. The chances of achieving that now look slim, but not completely impossible.

Then, a strange calm descended. MPs took a much-needed Easter break — this year April 19-22, and the week leading up to it.

The media temporarily removed the tents on College Green that were themselves supposed to be temporary. There they had reported on events across the road inside Parliament, and interviewed politicians dragged (willingly) out of it. They will return again. And again.

Attracted by the cameras, protestors had flocked to College Green to create a visible and vocal backdrop: either to accuse politicians of selling out the 2016 referendum result, or to accuse Leavers of lying and cheating, and to demand a new referendum. They too withdrew. They too will be back.

Brexit continued to bubble under the surface. Immediately after Easter, it sprang to life again, with talks resuming between the Conservative and Labour parties, the same old demands to change the proposed deal with the EU, a new demand for Theresa May to be sacked, this time from grassroots branches of her party, and new parties created by Brexit announcing their candidates for the May 23–26 elections for the European Parliament.

Although the EU described the postponed deadline as an opportunity for the UK to reflect on what it really wants, the extension has actually added to the workload now that Britain has to participate in those elections, even if the winners might not take their seats.

Using the pause for a moment of reflection, these are five thoughts on what happened in the last couple of years and on what lies ahead. Several have been discussed before. They all contain new developments:

- after all the frantic to-ing and fro-ing, almost nothing has changed for Britain

- nearly three years of political debate has failed to produce better-informed arguments

- if those past three years were bad, what lies ahead is going to be worse

- Theresa May’s handling has been disastrous but she might still get what she wants — just

- simplistic definitions of democracy and sovereignty are unhelpful

1. After all that, little has changed

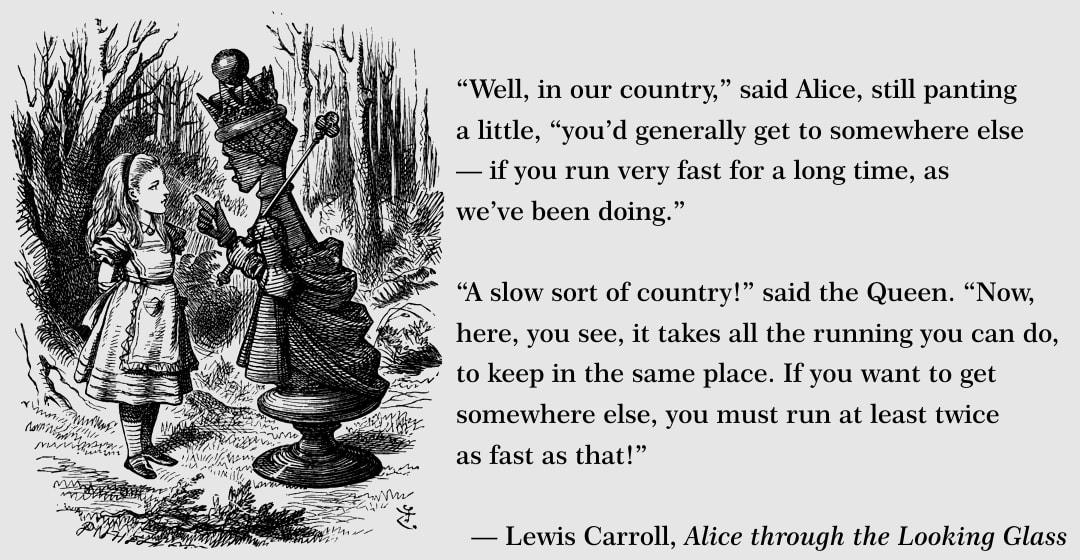

It’s a bit like the Red Queen’s race. The more you run, the more you stay in the same place. Months of frantic efforts, in Westminster, in multiple negotiating sessions in Brussels, and in high-level visits to various European capitals — they all take the UK more or less nowhere.

Britain still doesn’t know what kind of Brexit it wants, only that it voted in 2016 to leave the EU. And it still faces a chaotic departure with no deal with the EU, if it can’t get its act together. All that’s changed is the date. Brexit day has been moved from March 29 to October 31, 2019. Here’s why.

Theresa May spends almost two years in tough negotiations with the EU. They agree on a 585-page text on leaving the EU (the “Withdrawal Agreement”, explained here, here and here). It will be legally binding if it’s ratified. With it is a 26-page non-binding outline for further talks on the future relationship (the “political declaration”).

At home, her focus is on keeping her Conservative Party onside, not the country. Especially troublesome are over 50 hardline Brexiters. Even so, she knows the proposed deal is unpopular both in her party and in the country. She keeps procrastinating as events become increasingly frantic. First, October passes, then November, Christmas and the New Year, until she can delay no longer.

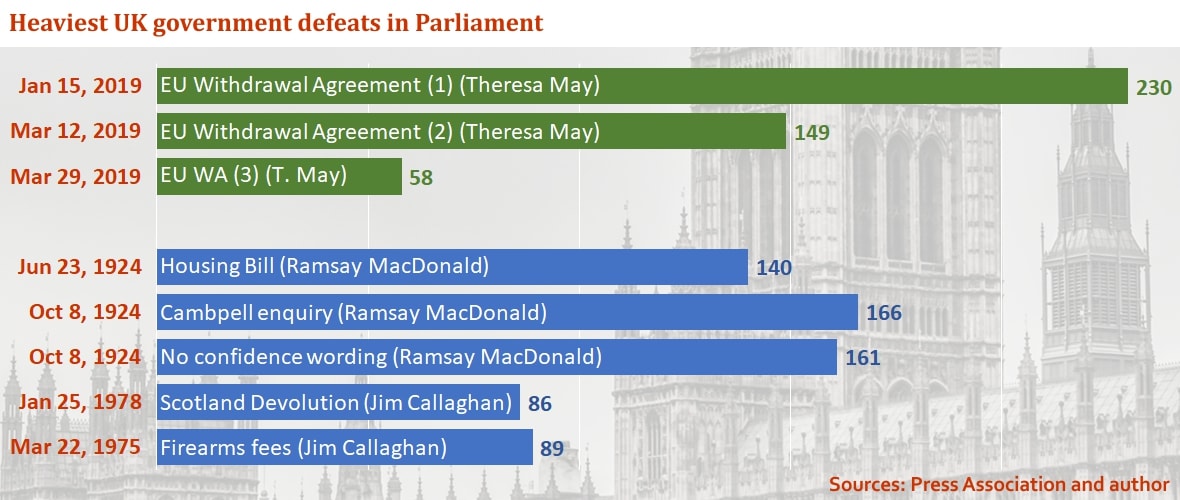

She finally puts the deal she negotiated to a vote in the House of Commons (the lower house) on January 16. It’s defeated by 432 to 202, a massive majority of 230, the largest defeat for a sitting government in British history. Large numbers of her own party vote against it.

Most governments would have resigned. Not Theresa May. Her tactic becomes clearer. She is playing a dangerous game. As the March 29 departure date approaches, she prepares to resubmit her deal to Parliament. The risk is that if Parliament keeps rejecting the deal, the UK will leave the EU with no agreement at all. Most experts (except a minority) predict this will be disastrous.

May is saying: agree my deal or risk crashing out. Or sometimes alternatively, agree my deal or risk staying in the EU and face the blame for betraying the wishes of voters in the June 2016 referendum. Either way, she persists single-mindedly with her one option.

May tightens the screw. On March 12, just 17 days before Brexit day, she resubmits her deal with some additional non-binding documents. Again it’s defeated, this time by 391 to 242. The majority of 149 still makes it one of the largest government defeats in recent history.

May concedes she has to ask the EU to agree to extend the deadline. Even if the deal passes, time will be needed to prepare the laws to implement it, and the European Parliament also has to approve it. On March 20, she proposes June 30. The EU says either May 22 if the deal is approved, or April 12 if it isn’t.

These dates relate to the election of a new European Parliament. April 12 is when the UK should tell the EU it will hold its elections. Voting is on May 23–26; the parliament’s inauguration is on July 2.

Meanwhile, there are two new developments.

One is a bombshell, from John Bercow, the speaker (chair) of the House of Commons. As it becomes clear May will receive nothing new from the EU, he digs up a 500-year-old convention (from 1604) saying he cannot accept an identical motion submitted a second time (see full statement and video extract). May’s supporters, who already accuse him of bias, are furious.

The other is the House of Commons itself. MPs vote to take matters into their own hands. They are concerned about the deadlock, dangers of a “no deal” Brexit, and May’s own handling. If May’s deal cannot not pass, they will take “indicative” votes to test what solution might win a majority.

On March 29, May resubmits the 585-page Withdrawal Agreement but without the non-binding political declaration. Bercow accepts it as an altered motion; the House of Commons rejects it — again. This time the vote is much closer, 344 to 286, a majority of 58. If May keeps trying, will she get her way in the end?

By now the House has voted to order May to request a further extension of the Article 50 deadline, if the Withdrawal Agreement stays rejected (as it does). On April 5, May asks the EU again for an extension to the end of June (this time to the 29th). This pushes further away the risk of no deal.

The EU is split between a short or a long extension, to the end of June or to the end of the year or a few months after. It agrees a compromise: October 31. (Cue jokes about a “Halloween Brexit”.)

Meanwhile, the “indicative” votes in the Commons confirm that none of the proposals has majority support. The political process in Britain over Brexit is well and truly log-jammed.

For the first time, in almost three years in office, May tries talking seriously to the opposition. Leaders of the governing Conservative Party and the opposition Labour Party begin the search for a way for the Withdrawal Agreement to pass Parliament. Achieving that would mean the government accepting a number of Labour positions it has previously rejected outright, including putting the deal to another referendum.

As the talks approach Easter, the two sides report some progress and some so-far insurmountable differences. This is not surprising.

Next: Dishonesty and trade-offs

__________________________

Find out more

- Article 50 two years on (The UK in a Changing Europe, 2019)

- Negotiating Brexit: Preparing for talks on the UK’s future relationship with the EU (Institute for Government, 2019)

- Brexit: A Love Story? (Audio — a highly recommended series of BBC Radio Four podcasts, 2018–19)

__________________________

Previous articles on Brexit

- And I leave you with Brexit (again), as it heads into ever darker hours (December 21, 2018)

- Five days of mathematical impossibility in the parallel universe of Brexit (October 19, 2018)

- When complexity challenges public opinion and democracy. Part 3—Brexit, two years later (June 22, 2018)

- Can a UK-EU Brexit deal really emerge from this chaos? (June 27, 2017)

See also the author’s blog

Peter Ungphakorn is based on the shores of Lake Léman in Switzerland. He spent almost two decades with the WTO Secretariat, Geneva. Before that he worked for The Nation and the Bangkok Post. He now writes for IEG Policy on agricultural trade issues and blogs on trade, Brexit and other issues at https://tradebetablog.wordpress.com/. He tweets @CoppetainPU.