Peter Ungphakorn

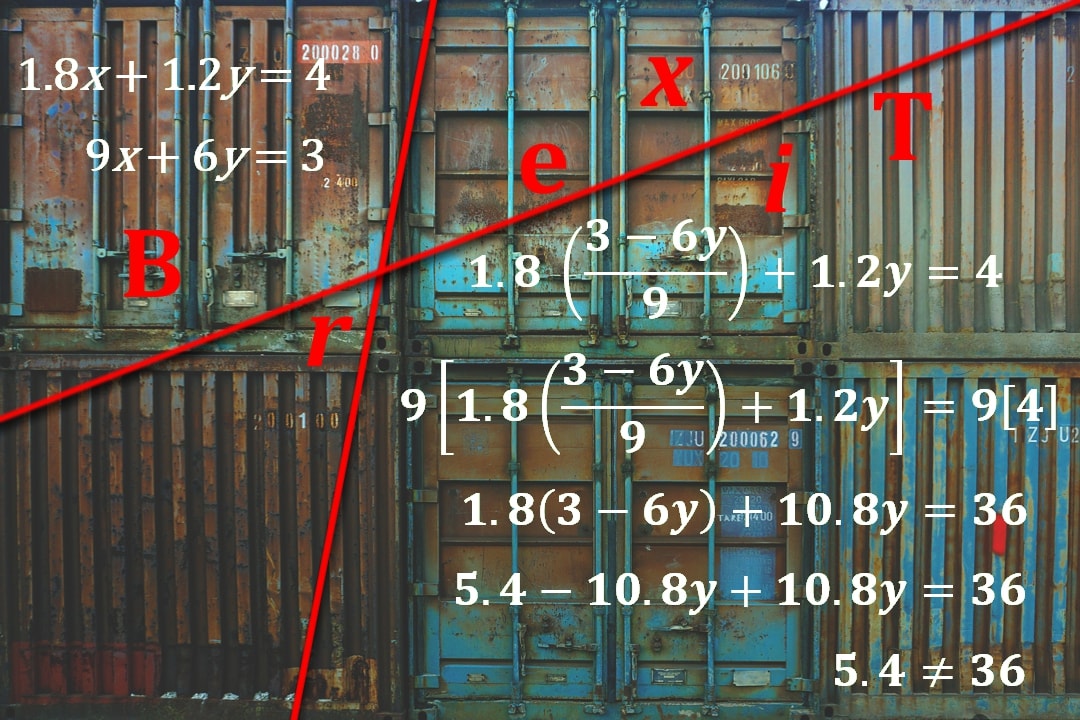

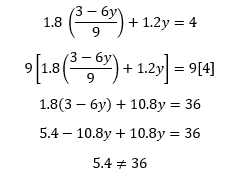

PREAMBLE. I promise this is not about mathematics, but I will start with a couple of equations. The point should be easy to understand.

What are the values of x and y, if

![]()

and

![]()

Mathematicians know immediately that there is no answer. We might even try to work it through like this, and there’d still be no answer:

You don’t have to understand the maths. Just look at that last line. It proves there is no answer because 5.4 cannot equal 36 unless we’re in some strange parallel universe.

And a strange parallel universe is exactly where Britain finds itself this week, described by the media as a crunch week for — you’ve guessed it — Brexit. No apologies for returning to this conundrum again.

SUNDAY MORNING. October 14. We wake up to a politician saying something on the radio that sounds awfully like those equations.

And I start writing this, feeling like an author beginning a novel without knowing what the end is going to be. Except it isn’t a novel. It’s real life. And it’s big.

Two weekends ago campaigners against Britain’s departure from the European Union (Brexit) took their pets on a march to demand another referendum. They called it a “wooferendom”. Next weekend will be much more serious. They plan a large demonstration in London with protestors from all over the country.

And at the heart of this, pressure is mounting even more, with talk of ministers resigning from the Cabinet, and Prime Minister Theresa May desperately trying to scrounge enough votes in Parliament for a Brexit deal that no one likes and might not be agreed with the EU.

This week is described as a make-or-break week for Brexit.

Except that the make-or-break time was supposed to have been a month ago. And the real make-or-break time might be in November or even later. You never know.

What we do know is that it’s month by month because that’s when EU heads of government can meet, and when British Prime Minister Theresa May can discuss Brexit with them.

We also know that make-or-break cannot be postponed forever. Britain has triggered the legal process of its separation (known as “Article 50”), meaning it has to leave the EU on March 29 unless the process is stopped.

Before that happens, any deal with the EU on the terms of the departure (the “Withdrawal Agreement”) plus any outline of the future relationship (a “political declaration” on what they will negotiate) must be presented to the British and European parliaments.

Meetings this week ought to produce those two documents. Failing that, November might be the absolute last chance. Or December.

But if the UK is leaving anyway, what is there to make or break? Isn’t it just “break”?

If only it were so simple. Sadly there are still British voters who do think it is.

“Just break” would be catastrophic. The UK and EU have each produced a long list of papers describing what might happen if there is no agreement at all, with advice for businesses and citizens on what to do — everything from no more flights between Britain and EU countries, to a shortage of medicines as imports crash into trade barriers erected overnight.

Britain has appointed a new minister to deal specifically with the risk of food shortages. Traffic on two of the motorways to the port of Dover is being disrupted or diverted as diggers start work on widening it. Why? To allow for kilometres-long queues of trucks waiting to be checked by customs and other officials before they cross to France. Right now there are no checks at all.

That can all be avoided — or at least delayed — if there is a deal on the terms of Britain’s withdrawal, and on what talks on the future relationship might aim for.

The proposed withdrawal terms cover a wide range of issues, from how much Britain should continue paying to the EU under various budget commitments made before its departure, to preserving rights for British and EU citizens living and working in each other’s territories under present rules allowing freedom of movement.

They also include a transition period from Brexit day next March until the end of 2020. For various reasons, the future relationship cannot be negotiated in detail until the transition begins. But a political declaration is supposed to set the direction.

Although there are signs those two documents could be agreed when May meets her EU counterparts on Wednesday (October 17), nothing is certain and tension is mounting.

SUNDAY AFTERNOON. The Brexit world is now swinging between optimism and pessimism. Time to explain why those equations are relevant.

In a speech in early 2017 (explained here), May set out 12 objectives for her Brexit negotiations. They boil down to these red lines, which must not be crossed. Britain must be free to

- control immigration — the EU’s internal or single market requires “freedom of movement” meaning member states have little power to control migration within the EU

- have its own trade policy and negotiate trade deals with other countries — currently pooled under the EU’s common commercial policy and customs union

- escape from EU law and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) — a requirement of EU membership, for example the ECJ rules on whether member states’ laws comply with EU legislation

- stop paying contributions to the EU budget

- keep a frictionless border between Northern Ireland (in the UK) and the Republic of Ireland (in the EU). Strictly speaking May’s red line is for no checks on people crossing the border but she has also accepted the red line of Ireland and the EU for no checks on goods and no border infrastructure. This is a condition of the fragile peace deal on the island of Ireland, signed in 1998 which led to all controls to be removed after about seven years. The border is now all but invisible.

The red lines are contradictory, like a set of equations that has no solution. There was nothing in the June 2016 referendum to say that voters voted for all of them. But May and the hard-line Brexiters insist all of them were in voters’ minds, even if not on the ballot paper.

Remove one or two and a solution is possible. For example, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland are outside the EU but have definitely blurred the first and third of those red lines in order to trade more closely with the EU.

Keep them all, and the only solution is for 5.4 to equal 36 (which it cannot).

The British premier’s approach has been to try to please everyone, at least among her own party’s squabbling MPs. And that means sticking as closely as she can to those red lines.

It also means observing a sixth red line — from the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Northern Ireland.

May’s Conservative Party does not have a majority in Parliament and needs the DUP’s 10 MPs to make up the numbers. The DUP insists there should be no border down the Irish Sea, between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK and at crucial moments has blocked proposals that would involve goods inspections between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

Dozens of ideas have been put forward to try to solve the puzzle, many extremely intricate. All of them involve blurring one red line or another, or perhaps delaying some red lines in order to keep one of them alive (the invisible Irish border).

Suddenly, May’s attempt to please everyone is having the opposite effect. Rather than keeping her party together, key ministers have resigned and today, former Brexit Secretary David Davis has called on others to follow him out of the Cabinet.

Her withdrawal proposal based on those red lines is so unpopular among hard Brexiters and those who wanted to stay in the EU alike, that it doesn’t seem to have enough support in Parliament. In fact, experts say it’s possible that none of the options being discussed would have majority support among MPs.

Worse, the mess has raised the prospect of the whole of the United Kingdom disintegrating. Scottish nationalists are growing more confident that the mishandling could push voters to support their own independence.

May’s attempt to keep everyone together could actually cause everything to fall apart.

SUNDAY EVENING. Britain’s Brexit minister Dominic Raab has flown to Brussels for unscheduled talks. News breaks that agreement has been reached. Then news breaks that it hasn’t. The chances of agreement on Wednesday seem to recede. Disagreement continues over a “backstop” on Northern Ireland. What is it?

This is about the most difficult challenge among those red lines: how to keep the Irish border frictionless.

A decade ago, paramilitary Irish nationalists were largely persuaded to lay down their arms and explosives because the invisible border went some way towards their aim of a United Ireland while keeping the north in the UK. Anything built on the border might be too big a temptation for them.

Ironically, arrangements to avoid checking people are simpler. The problem is goods, including agricultural products and live animals. Checks are not needed now because the UK and EU have identical internal health standards, controls and inspections.

One of the objectives of Brexit is for the UK to have its own rules, regulations and standards. But to avoid inspection when the goods cross the border requires identical conditions, or formal recognition that the conditions are equivalent enough to be considered identical.

To do this for the full range of products and in all situations is pretty complicated — goods crossing the border range from butter and cheese from processing factories to sheep and cattle roaming across the line on farms that straddle the border.

One solution: keep Northern Ireland in the EU customs union (so no import duties are charged) and applying the EU’s rules and regulations instead of the rest of the UK’s to avoid checks. Result? Checks set up on trade between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK — the DUP’s red line is crossed.

Another: the whole of the UK stays in the customs union and applies EU regulations. Result? Two of May’s red lines are crossed (independent trade policy and laws).

A third: forget the frictionless Irish border. Some hard Brexiters claim the problem with the border is exaggerated. Most experts on the Irish problem dismiss this as ignorance of what the mood is in Northern Ireland and how dangerous that would be. (This moving video, “My Dad, the Peace and Me”, shows why.)

So among the ideas London and Brussels are discussing is a “transition” period in which the UK would stay in a customs union (having same duties on imports from outside the UK and EU and none on trade between them).

This would allow the Irish border to stay invisible (provided the issue of product standards is also solved), avoid sudden congestion at ports such as Dover, and give the UK and EU time to negotiate whether to have some form of free trade agreement over the longer term.

But, for the Irish border, it gets more complicated. London argues that technology can be used to eliminate the need for any checks at the border, from electronic paperwork to blockchain.

The EU says some of the needed technology doesn’t exist — it’s certainly not used in full on any border in the world.

The upshot is the UK expressing the intention to set it up, and the EU insisting on a “backstop” as insurance — a customs union arrangement with regulatory alignment either for Northern Ireland alone or the whole UK. This is a backstop because it would guarantee a frictionless border even while the technology is unavailable.

Either of those is going to cross at least one red line. The hard Brexiters are up in arms because the “backstop” would not have a definite end point — only until the technology is implemented, which might be never. They claim it’s an EU plot to keep Britain in its clutches indefinitely, a conspiracy theory with little hard evidence.

With that kind of debate the insoluble equations simply multiply.

And that’s more or less how Dominic Grieve, former Attorney General, and pro-Remain Conservative politician, had summed it up in the morning on BBC Radio Four:

“David Davis has highlighted that if we remain in a customs union, it is a form of dependency, it preserves our trade and manufacture, which is tremendously important, but it has other drawbacks.

“The prime minister is trying to square the circle, trying to maintain the union of the United Kingdom, which is very important to her, particularly in the Northern Ireland context at the moment, and is trying to ensure that we honour our obligations under the Good Friday Agreement, and that we achieve a deal which isn’t hugely damaging to our economy.

“And neither of these versions, I’m afraid, I think, is likely to succeed. The prime minister’s is the safer version, but it has the drawbacks that David Davis identifies.”

MONDAY. The day after the night before. There was no agreement on Sunday and as expected, the “backstop” was the problem. Now, there’s even a “backstop” to the “backstop”, but let’s go into that.

British and EU political perspectives are so different. One BBC journalist in London said: “I can see no way through without Theresa May leaving a considerable amount of political blood on the floor”.

His colleague across the English Channel said: “The ‘drama’ being reported in UK over yesterday’s impasse in #Brexit negotiations is absent in Brussels.”

What’s more, reports from Brussels say there won’t be any more talks among officials until heads of government meet on Wednesday.

Some speculate that there might actually be a possible solution, but it will need political leaders to decide. Others suggest any deal might have to wait until December.

I won’t bet on it, but I may have nothing to say on Tuesday.

TUESDAY. At least that prediction is almost correct. The media report that a small group of ministers, some of them potential rebels, met on Monday evening in someone’s office to share a pizza or ten.

The Cabinet met this morning and ministers reportedly agreed to hold fire, allowing May to keep trying with the EU in the hope that continuing talks will produce a deal that keeps her insoluble equations intact, but after the Wednesday summit. Later, EU leaders reportedly agree that they won’t issue a statement at Wednesday’s summit.

One rumour is that the UK might decide the drop for its insistence on an actual end date for the “backstop”, and propose instead the criteria for ending it. Hey-ho.

WEDNESDAY. The German and French governments announce preparations for no deal. For France, that might mean requiring British visitors to have visas, but the impact of “no deal” will be much, much more.

Theresa May heads for Brussels. Little more is expected to happen until she meets the 27 other EU leaders (technically she’s still one of them) this evening.

THURSDAY. And so “crunch time” turns out to be empty. They met, they talked, they agreed nothing. Even the special summit meeting in November has been dropped from the schedule, although it could still happen if there is progress between now and then.

Theresa May emerged today talking about possibly extending the transition period for a few months — the present proposal is from March 29, 2019 to the end of 2020. This would give the UK and EU more time to talk and delay the need for a “backstop”. Pro-Brexit politicians are furious.

As journalist Ian Dunt wrote this morning: “That’s what it’s like when you let the lunatics take control. The basic conditions of sanity are precisely those which can never be countenanced.”

Peter Ungphakorn is based on the shores of Lake Léman in Switzerland. He spent almost two decades with the WTO Secretariat, Geneva. Before that he worked for The Nation and the Bangkok Post. He now writes for IEG Policy on agricultural trade issues and blogs on trade, Brexit and other issues at https://tradebetablog.wordpress.com/. He tweets @CoppetainPU.