Peter Ungphakorn

Sometimes television can surprise. Programmes that few thought would reach beyond a handful of enthusiasts can take off and attract huge audiences.

For over two million viewers in Britain, cold grey January evenings have been brightened by a week of hour-long programmes called Winterwatch, broadcast live from a nature reserve.

It’s hosted by three enthusiastic experts with a sense of fun and great story-telling skills, without ever dumbing down on some pretty serious scientific content. With contributions from naturalists and conservation societies, the programme is a mix of informative and entertaining live coverage, 24-hour hidden cameras some with night-vision, filmed inserts, and audience contributions, including photos, videos and participation in surveys of wildlife in people’s gardens.

The latest series included a “Game of Crows” segment, imitating the well-known fantasy drama series. Here, two types of crow were tested to see which was more intelligent (spoiler: the ordinary crow just beat the raven but both were impressively clever).

You can watch some highlights of the stunning photography here.

Two to three million viewers in the UK is a decent size for all but the biggest attractions but a few years ago a programme like Winterwatch would not have been considered at all.

The programme grew out of the popularity of Springwatch, which began in 2005 and now runs for three weeks in late May and early June. It includes live coverage of various types of birds nesting, as their young hatch and eventually leave home.

Autumnwatch began the following year, a series that has featured vicious fighting (“rutting”) as stags competed for females. And then in 2013 came Winterwatch in a season not usually associated with wildlife watching.

The three “Watch” series air on BBC2, a channel designed more for a special-interest audience than the mass-market BBC1.

Nature programmes by David Attenborough, such as the Blue Planet series, which are award-winners and worldwide best-sellers, are on BBC1.

Blue Planet II’s audience in the UK reached 14 million. Springwatch and its siblings will never get anywhere near that, but they still have a solid following.

One of the interesting questions is whether these programmes would ever have been created outside a public broadcasting corporation like the BBC. Investing in niche programmes like these could be too risky for commercial companies.

BBC2’s biggest unexpected success in popularising an unlikely subject was in a sport. It pioneered televised snooker in the 1960s, at that time seen as the opposite of everything that would make good TV, with its whispering commentators, hushed spectators and excitement suppressed.

Few expected it to last. The controller of BBC2 at that time thought it might. He was none other than David Attenborough, and televised snooker is still going strong half a century later.

Less successful were a series of programmes on sheepdog trials — shepherds and their dogs competing to corral sheep through a number of obstacles. They are no longer on national television, but they survive on Alba, the BBC’s Gaelic-language channel for Scotland.

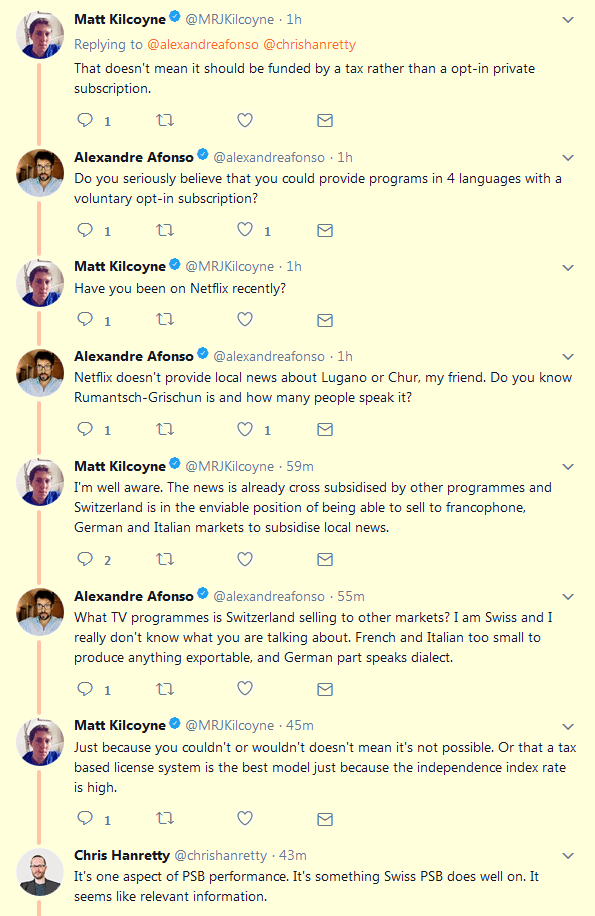

March 4 crunch in Switzerland

The question of whether public broadcasting is needed to serve minority interests is one of several issues now confronting voters in Switzerland. The national public broadcasting service is funded, like the BBC, by a licence fee. It’s under threat, and March 4 is the crunch date.

Switzerland holds referendums and votes on popular initiatives three or four times a year under the Swiss system of direct democracy. This year’s first vote is on March 4. Of the two topics put to the vote nationally, the most controversial by far is an initiative by the right-wing Swiss People’s Party, supported by some commercial enterprises and with the 100,000 signatures required to trigger a vote.

The initiative is called “No Billag”, referring to the organisation that collects the licence fee. If successful, the initiative would scrap the fee, probably depriving the national broadcaster of most of its revenue and probably decimating it. (To avoid confusion, the question on ballot papers has been carefully re-phrased as “Yes to the initiative”.)

Supporters of the initiative say the nature of media has changed. The public now has many options for viewing and listening, and commercial companies should be freer to compete to provide broadcast-to-air, cable, online and on-demand services. Compulsory payments for a national broadcaster are unfair to those who don’t watch or listen to the programmes, they argue.

Supporters of the licence fee counter that a national broadcaster is needed to preserve the national identity, cohesion and culture, for “media plurality”, and to serve minority as well as majority interests.

This is why folk performers such as yodellers and alphorn players have joined forces with rappers among 5,000 artists and 50 organisations opposing the initiative.

It “not only calls into question the freedom to form opinions, but also the cultural tradition in Switzerland: from folk music to techno, from detective series to movies, from thrillers to comedy festivals,” they said.

Commercial broadcasting will not cater for minority tastes, critics argue. What’s more, public broadcasting needs to serve mass audiences, in order to have the skills, resources and economies of scale to produce good, diverse minority programmes as well.

The government opposes the initiative and both chambers of the national parliament have voted against it.

Similar arguments for and against a licence-supported broadcaster have been heard in Britain and other countries with similar systems. In the UK the debate has been about whether the BBC is unfairly dominant. The outcome has at most been some additional constraints on the BBC, eroding slightly its position in the market.

The March 4 vote in Switzerland is more drastic. No erosion here. Essentially this is about the life or near-death of the national broadcaster. The signs are that voters will rescue it, but no one is taking anything for granted.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” admin_label=”box” background_color=”#eaeaea” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#969696″ border_style=”solid” custom_margin=”|10px||10px” custom_padding=”10px|10px|10px|10px” disabled=”off”]What is public broadcasting?

Wikipedia says “the British model has been widely accepted as a universal definition” with these principles:

· Universal geographic accessibility

· Universal appeal

· Attention to minorities

· Contribution to national identity and sense of community

· Distance from vested interests

· Direct funding and universality of payment

· Competition in good programming rather than numbers

· Guidelines that liberate rather than restrict

“… Within public broadcasting there are two different views regarding commercial activity. One is that public broadcasting is incompatible with commercial objectives. The other is that public broadcasting can and should compete in the marketplace with commercial broadcasters. This dichotomy is highlighted by the public service aspects of traditional commercial broadcasters.

“Public broadcasters in each jurisdiction may or may not be synonymous with government controlled broadcasters. In some countries like the UK public broadcasters are not sanctioned by government departments and have independent means of funding, and thus enjoy editorial independence.”

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” admin_label=”Text” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid” disabled=”off”]

March 4 voting papers: two federal questions, one cantonal in Vaud, and official booklets summarising the issues and the parties’ positions | Peter Ungphakorn

Expensive licence fee

Public broadcasting exists around the world in vastly different forms. Among OECD countries, the US has perhaps the weakest. Some are funded by licence fees, where the money can only go to the broadcasters, to keep them independent from government; others use different sources including tax.

Switzerland has a licence fee, but the situation is different from other countries in a number of ways. Cultural identity is particularly important because the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (SBC) has to serve four language regions as well as diverse tastes.

It has seven major free-to-air TV channels — three in German, and two each in French and Italian — plus some local or specialist channels, and a few TV programmes in Romansh (the fourth language).

It has six main German radio stations, four French, three Italian and one Romansh. Those for the three larger language populations specialise in talk, classical music and culture, and pop music).

Some foreign TV stations are can be received on digital free-to-air, for example French channels are available in French-speaking Switzerland. There are numerous commercial radio stations, mainly broadcasting various types of pop music, and a few local TV stations. Many Swiss subscribe to cable services, which have many additional local and foreign radio and TV stations (including the BBC).

All of this for a population of around eight million, considerably less than the 14 million viewers who watched the first episode of Blue Planet II in Britain (population about 66 million).

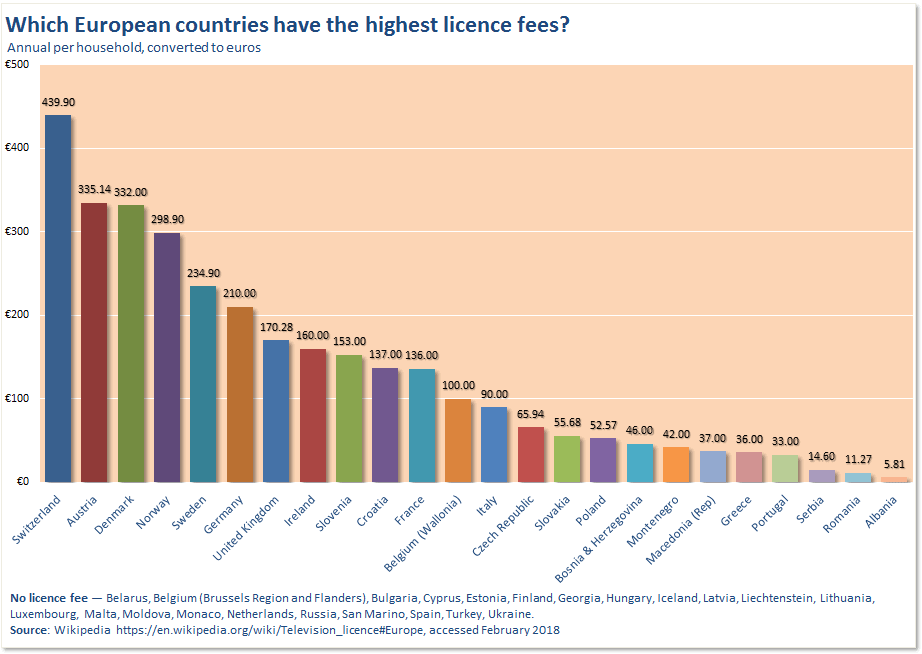

To fund all of this, the Swiss licence fee is therefore the most expensive in the world. For radio and television it is CHF451.10 per year per household (almost US$490), higher for companies, although this is set to fall to CHF365, one franc per day, in 2019.

In 2016, the licence fee brought in CHF1.37 billion ($1.46 billion). Out of that, CHF67 million (about 5%) was shared with commercial broadcasters (increased to CHF81 million in 2017). (A full breakdown is here.)

The distribution includes cross-subsidy by the larger German speaking area (73% of money raised, 43% of money spent) to the three other zones.

The corporation’s income is topped up with advertising on national TV, but unlike in most European countries, it carries major sports such as Champions League football free-to-air.

By contrast, the £147 ($206) per year British licence fee is less than half the Swiss one. But since the UK’s population is eight times that of Switzerland, this is enough to fund the whole BBC without any broadcast advertising inside the UK.

The BBC can also afford to produce many more dramas, documentaries and other programmes that are popular enough to sell around the world. At best Swiss TV and radio can participate in co-production with other European broadcasters to do that.

Licence fees elsewhere in Europe are around €335.14 ($415.95) per year in Austria (the actual amount varies according to state); NOK2,834.70 ($365) in Norway; €210 ($261) in Germany; €136 ($169) in France; €90 ($112) in Italy; all the way down to zero in the Netherlands (funded by taxpayers directly through the government’s budget, by advertising and by some membership contributions, under a very different system of public broadcasting, which has seen a number of recent upheavals).

Is the cost worth it?

The key questions facing the Swiss are: how important is it to have a national broadcaster? And is it unfair to ask people who don’t watch it to pay for it?

One underlying issue is whether broadcasting is a right for commercial operators. It’s an argument about who owns airwaves and bandwidth — whether they are public resources that should only be given to the private sector as a limited concession; or whether they are like any other commodity, best left to market forces perhaps within a framework of regulation.

It’s a market, says Céline Amaudruz of the Swiss People’s Party: “The privileges granted to the SBC make it a quasi-monopolistic company.”

It’s not, says Guido Keel, head of the Institute for Applied Media Studies in Winterthur: “Journalism is a public good. Its benefits cannot be limited to those who pay for it. Media informs society so that it can participate in democratic and thus state-building processes. This enables the media to create democracy, and those who don’t pay for media use will benefit from it,” he says in an explainer on swissinfo.ch, the national broadcaster’s website.

Social Democrat parliamentarian Tim Guldimann calls the initiative an attack on Switzerland and public services in general.

“‘No Billag’ would not only eliminate SRF [radio] programmes such as ‘Echo der Zeit’ [a current affairs programme], it would also constitute a full-on attack on the up-to-now uncontested belief that the state should tackle social issues that the market ignores,” he writes.

Related to that is whether it’s possible for commercial companies to produce the same kind of content as the national broadcaster.

Private broadcasters can be regulated, to require them to produce impartial national news, diverse programming and so on, but it’s unclear how effective that will be. International experience is not promising. Could a Switzerland without a national broadcaster avoid opinionated private TV along the lines of, say, Fox News in the US? Many see that as a real danger, although the regulations in Switzerland would probably be different.

Competition in broadcasting rarely drives the kind of innovation that created Springwatch and televised snooker, and more generally “merit programming”.

In a PhD thesis, Chris Hanretty was pessimistic “about the capacity of private suppliers to supply large amounts of merit programming”.

His focus was on the political independence of public broadcasters as an essential contribution to democracy, combatting corruption and promoting the rule of law:

“Although they provide many other types of content, public service broadcasters are noted for providing news and current affairs programming. This content provides a source of information for evaluating the alternatives put to us in competitive elections.” (Page 13)

Innovation in commercial broadcasting is usually only in mass audience programmes such as block-buster series. Or when pirate radio stations forced the BBC to loosen up and create a proper pop music station (Radio 1) in the 1960s followed by legal commercial stations.

Otherwise, commercial broadcasters tend usually — but not always — to keep to the safe middle ground rather than compete to break new ground. In Britain, BBC Radio 3 includes cutting-edge classical, jazz and world music alongside more conventional material, whereas the commercial Classic FM tends to stick to more popular works. There are no Swiss commercial classical music or jazz stations.

You only have to go to a country where the whole FM bandwidth is crammed full of commercial stations to see that listeners can be offered less diversity than in countries with national broadcasters and fewer commercial stations. As economists have noted, commercial competition often means everyone converging in the middle.

There are commercial channels like Discovery, National Geographic, Planète+ or Animaux (the latter two in France) but round-the-clock documentaries don’t have the same impact as a programmed schedule — such as BBC2 starting the evening with high-brow quiz competition for university teams followed by Springwatch, a history documentary or modern drama, a political comedy show and an in-depth news programme.

Fast changing nature

On the other hand the very nature of broadcasting is changing. Increasingly viewers choose when and what to watch or listen to, for themselves. They go to Netflix, Youtube, Spotify, Tidal, or other on-demand or streamed services (some pirated). But it might need a regular channel to produce a series first (such as HBO making Game of Thrones) and to gain publicity before viewers seek the on-demand version.

Large broadcasters are responding with their own on-demand services such as the BBC’s iPlayer (the Swiss broadcaster has its own version) but the content is normally confined to their own material.

They have also created their own web portals:

“The BBC News website is the eighth most visited in the world, and the second most-visited news site (the first is Fox News). Italian [public sector broadcaster] Rai has been less successful: it lags behind other domestic telecoms groups (Telecom Italia; Wind; Kataweb; RCS) but stills beats its commercial competitor Mediaset.” (Hanretty, page 327)

Two final thoughts. First, the public is a lot less enthusiastic in Japan according to the Economist, which described the broadcaster, NHK, as “snoringly boring” apart from the fact that it’s the only channel to show sumo.

“Many people refuse to pay because they don’t watch NHK, often out of distaste for its pandering to the government,” it reported. This may underscore the need for public broadcasting to be genuinely independent.

Meanwhile, an experiment in the UK showed that many who started off reluctant about the licence found they missed the BBC after switching it off for nine days.

“I just thought the licence fee was another tax, and not good value for money,” said one in the Guardian’s report. “Being without the BBC was absolutely dreadful, just awful. I just didn’t realise how much we watched it.”

If they vote to scrap their licence fee, the Swiss might discover that you don’t know what you’ve got until you lose it.

Update: On March 4, the nationwide proposal to scrap the TV licence in Switzerland was rejected by all cantons, and by 71.6% to 28.4% of the popular vote, turnout 54.1%. Majorities in favour were needed on both counts

Finally, try it

It’s not for everyone, but you can sample or watch the whole of BBC’s Winterwatch 2018. Clips are here. Or watch an episode:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=dr8FZk0RFpU

Peter Ungphakorn is based on the shores of Lake Léman in Switzerland. He spent almost two decades with the WTO Secretariat, Geneva. Before that he worked for The Nation and the Bangkok Post. He now writes for IEG Policy on agricultural trade issues and blogs on trade, Brexit and other issues at https://tradebetablog.wordpress.com/

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]