Peter Ungphakorn Story

The end of the year has seen extraordinary twists and turns in British politics, and all because of Brexit. Peter Ungphakorn tries to make sense of what’s been happening, but gives up on predictions for 2019.

This is a kind of goodbye. A farewell to 2018 and a look towards 2019, when Britain is supposed to say “so long” to the European Union. It’s also the last monthly piece in this “Léman” column, although (if the editors are willing) the column might return from time to time, as events unfold.

And unfold they will in 2019 although what shape will emerge is pretty much unclear.

In 2018 the column has returned repeatedly to Brexit (Britain leaving the EU), the crisis in the World Trade Organization (WTO), and Swiss politics.

In 2019 the first two are unpredictable. The third ought to be predictable but even Swiss politics can be battered by events elsewhere.

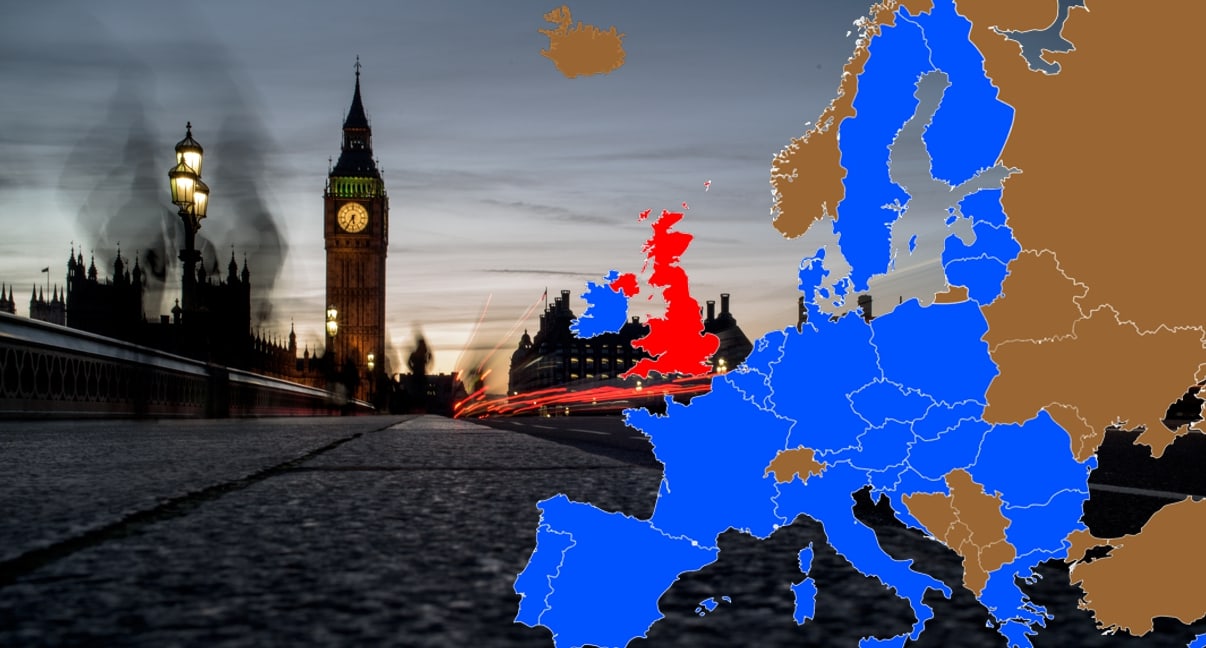

The most dramatic and the one that seems to sink ever deeper into chaos is Brexit. I return to it, again.

The meaning of backstop

In several previous articles I said that by the time the piece got published it would be out of date. That’s still true with this one, although the British Parliament is due to go on holiday this weekend so perhaps we’ll have a bit of peace on earth — British earth at least.

There has certainly been no peace in Brexitland in the past few weeks. And it promises to get worse in 2019 with time running out to sort out the first phase of Brexit before March 29, when the UK is due to leave the EU.

Let me try to sum it up.

On November 14, Britain and the EU agreed on a proposed Withdrawal Agreement, what journalists like to call the terms of the divorce. This was not a deal on their future relationship, which would still have to be negotiated over the next few years. Attached was (and still is) a non-binding political statement outlining in the broadest terms where that next phase of talks might head.

Following so far? An agreement needs two or more sides. EU heads of government endorsed it on November 25. It still needed the approval of the European and British parliaments. The vote in London was due on December 11. And that’s where the simplicity ends. Brace yourselves.

Then the Backstop hit the fan. Its odour had been steadily rising over the weeks and months. Its principles had already been agreed in December 2017. Suddenly, almost a year later, even ministers who at that time were in UK Prime Minster Theresa May’s cabinet forgot what they’d agreed to and declared its stench was terrible.

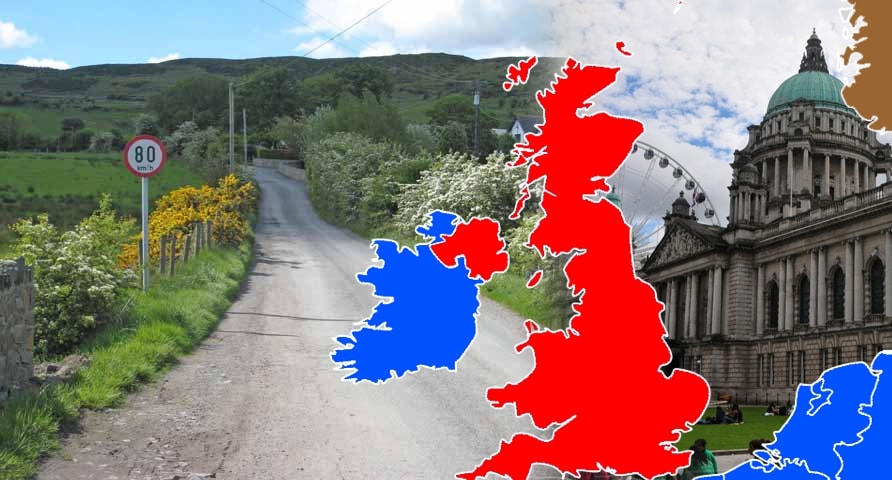

And all because of a vitally important issue, one that few thought relevant to UK-EU relations at the time of the Brexit referendum in 2016 — peace on the island of Ireland.

Few bothered to read the whole 585-page Withdrawal Agreement. Instead, they focused on the part called the “Protocol on Ireland / Northern Ireland”. It is itself a complex legal text, so few even read that.

The protocol is an insurance policy to ensure the Irish border remains completely open and invisible, whatever happens in the future between the UK and EU. It will only be used if the UK and EU fail to agree on something else that achieves the same result. It’s an agreement to fall back on, a “backstop”.

The purpose is to preserve the fragile peace that ended decades of bombing and paramilitary conflict, over whether Northern Ireland should unite with the Republic to the south, or stay in the United Kingdom. Keeping the border but making it invisible has been symbolic in pacifying both sides. There is a border. You just can’t see it.

How is this possible? A complicated mix of agreements. One allows people to travel freely across it. And so long as the UK and Ireland are both in the EU, they are part of a single internal EU market. So goods can flow freely between the two, just as they do between Manchester and Leeds or between Chachoengsao and Chon Buri.

The Backstop protocol tries to preserve as much of that as possible. How it does it is complicated.

Essentially the UK would charge the same import duty as the EU on products from outside the EU — there would be a “customs union” — and it would comply with many EU rules and regulations for trade in goods.

Northern Ireland would be even more closely aligned. For example, animals crossing the Irish border would not need to be checked since they would already meet the same veterinary health standards. But that would imply some differences between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, requiring checks on live animals and some products crossing the Irish Sea between the two.

Almighty row

This has caused an almighty row. Forget the fact that there are already checks, and that Northern Ireland is semi-autonomous (like Scotland and Wales). So a number of its laws and standards are not identical to the rest of the UK’s.

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Northern Ireland, which is aggressively for preserving union with Britain, complained bitterly that this meant Theresa May had fallen into an Irish-EU trap. It would push Northern Ireland away from the UK and the EU would ultimately annex it, some claimed.

The DUP threatened to tear up a deal that has given May’s minority Conservatives a majority in most votes in parliament

Hard-core Brexiters in the Conservative Party went even further. They said the backstop meant Britain would be a vassal state of the EU because it would have to align standards and have the same import tariffs without having any say in either of them.

Some grudgingly accepted the Backstop would be needed but insisted it had to be temporary, with either a fixed end date, or a provision allowing the UK to scrap it unilaterally instead of requiring the EU to agree as well.

One problem. In that case it wouldn’t be a backstop. It would no longer guarantee that if all else fails, peace will be preserved for as long as we can foresee in Northern Ireland.

Actually, it’s hard to find anyone who likes the Withdrawal Agreement. It has managed to unite those seeking a softer Brexit, Remainers (those who supported staying in the EU) and the hard Brexiters. All of them hate it. If it does pass Parliament, that will only be because enough MPs fear that the alternatives of “no deal”, or a Labour Party government, would be worse.

For now, Theresa May and a handful of her supporters in the Cabinet and her party are isolated. And yet something like the present draft is the logical outcome of the objectives and “red lines” she set out almost two years ago. The problem is and has always been the constraints of those red lines.

Three extraordinary days

Then came three of the most extraordinary days in British politics.

It all came to a head on Monday December 10, the eve of the vote on the Withdrawal Agreement. The government lost three big votes in Parliament, including one declaring it in contempt of the house for failing to comply with its demand to see a legal assessment of a key Brexit issue.

The prime minister was in deep trouble; her party was in turmoil. It was clear she would lose the vote on the Withdrawal Agreement the next day. Would there still be a vote? Would she survive? She and her ministers insisted the vote was going ahead. They continued to say that in interviews right into the morning of December 11. Then the vote was pulled.

Hard-core Brexiters in the Conservative Party quickly acquired the necessary number of signatures to call a vote of no confidence in their party leader. May looked well and truly doomed.

But just as suddenly, the mood started to change. She agreed to hold the party’s no confidence vote that very evening, on Wednesday December 12.

The hard Brexiters complained they had too little time to prepare. Others in the party lined up to announce their support for her. They didn’t exactly put it this way but what they meant was: better to keep her on, than to open the door to some fringe Brexiter with madcap ideas that would damage both the country and destroy the party.

She won by 200 votes to 117 but the hardliners still demanded her resignation.

Bizarrely, the atmosphere was now almost one of relief. And yet, despite those huge mood swings in just three days, nothing had changed. Nothing.

There was still no majority in parliament for the Withdrawal Agreement. There was no majority in parliament for any other possible outcome. Not for crashing out with no deal — the most damaging of all outcomes for the UK economy. Not for a softer Brexit keeping the UK in a close relationship with the EU similar to Norway’s. Not for returning the issue to the public for another referendum.

May eventually announced that the vote would be in the week of January 14, despite many MPs calling for her to hold it before the Christmas and New Year break. That will leave only two months to the March 29 leave date.

Complaints mounted from businesses that it was impossible for them to prepare without knowing what was going to happen. With time now so short, many just went ahead and moved some operations out of the UK and into the rest of the EU.

On December 18, the Cabinet announced £2 billion was being budgeted for departments to prepare for a damaging “no deal” exit that no one wants (except a tiny minority) and the government has said it wants to avoid at all costs. Three thousand soldiers were put on stand-by to deal with logistical chaos, and the government chartered a plane in case transport disruption prevented medicines reaching British hospitals.

2019

So what lies ahead in 2019? God knows. Perhaps the death of the Withdrawal Agreement even if May secures some reassuring and non-binding language from the EU on the backstop. She’s shown she’s a survivor by repeatedly kicking the can down the road, but she’s running out of road.

What then? A new prime minister? A general election and a new prime minister? A new referendum, a general election and a new prime minister (in any random order)?

If sanity prevails “Article 50”, the legal instrument for the UK to leave the EU, will be extended mainly to give the UK more time to sort out what it wants, and then to talk some more to the EU. Who knows? Article 50 could even be revoked and the UK would stay in the EU.

Either of those would have to happen before March 29.

Apart from anything else it would require British politicians to agree on something for a change. The bookies have odds for everything. Only a fool would put any money on anything.

And that’s it for now. Until next time, then. Whenever that is.

Peter Ungphakorn is based on the shores of Lake Léman in Switzerland. He spent almost two decades with the WTO Secretariat, Geneva. Before that he worked for The Nation and the Bangkok Post. He now writes for IEG Policy on agricultural trade issues and blogs on trade, Brexit and other issues at https://tradebetablog.wordpress.com/. He tweets @CoppetainPU.